Climate scientists have been saying for years that one of the many downsides of a warming planet is that both droughts and torrential rains are both likely to get worse. That’s what climate models predict, and that’s what observers have noted, most recently in the IPCC’s report on extreme weather, released last month. It makes physical sense, too. A warmer atmosphere can absorb more water vapor, and what goes up must come down — and thanks to prevailing winds, it won’t come down in the same place.

The idea of changes to the so-called hydrologic cycle, in short, hangs together pretty well. According to a new paper just published in Science, however, the picture is flawed in one important and disturbing way. Based on measurements gathered around the world from 1950-2000, a team of researchers from Australia and the U.S. has concluded that the hydrologic cycle is indeed changing. Wet areas are getting wetter and dry areas are getting drier. But it’s happening about twice as fast as anyone thought, and that could mean big trouble for places like Australia, which has already been experiencing crushing drought in recent years.

More than 3,000 robotic profiling floats provide crucial information on upper layers of the world's ocean currents. Credit: Alicia Navidad/CSIRO.

The reason for this disconnect between expectation and reality is that the easiest place to collect rainfall data is on land, where scientists and rain gauges are located. About 71 percent of the world is covered in ocean, however. “Most of the action, however, takes place over the sea,” lead author Paul Durack, a postdoctoral fellow at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, said in a telephone interview. In order to get a more comprehensive look at how water is exchanged between the surface and the atmosphere, that’s where Durack and his colleagues went to look.

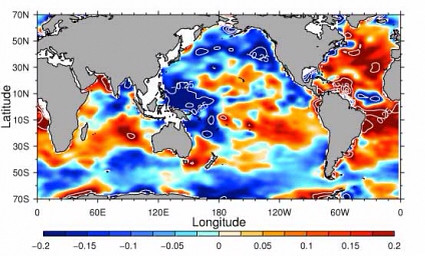

Nobody has rainfall data from the ocean, so Durack and his collaborators looked instead at salinity — that is, saltiness — in ocean waters. The reasoning is straightforward enough. When water evaporates from the surface of the ocean, it leaves the salt behind. That makes increased saltiness a good proxy for drought. When fresh water rains back down on the ocean, it dilutes the seawater, so decreased saltiness is the equivalent of a land-based flood. More

Water Security is National Security

Water resources and how they are managed impact almost all aspects of society and the economy, in particular health, food production and security, domestic water supply and sanitation, energy, industry, and the functioning of ecosystems. Under present climate variability, water stress is already high, particularly in many developing countries, and climate change adds even more urgency for action. Without improved water resources management, the progress towards poverty reduction targets, the Millennium Development Goals, and sustainable development in all its economic, social and environ- mental dimensions, will be jeopardized. UN Water.Org

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Climate Change Has Intensified The Global Water Cycle

Labels:

agriculture,

conflict,

security,

water,

water harvesting